Vanuatu: Tanna and the Jon Frum cargo cult

Vanuatu: Tanna and the Jon Frum cargo cult

The boy at the initiation ceremony, Tanna Island, VanuatuI hadn’t been looking forward to flying from Port Vila, Vanuatu’s capital, to Tanna Island,

200 kilometres south. The previous week, at midnight, a plane from Espiritu Santo Island

had crashed into the town’s bay during torrential rain. Half the passengers were killed on

impact, while, of the eight who escaped the sinking fuselage, only four, who had swum disoriented

for six hours in pitch darkness to the nearest land, had survived. As we flew over the

crash site itself, one of the passengers told me that the wreck had never been found and that

sharks had probably eaten the missing bodies.

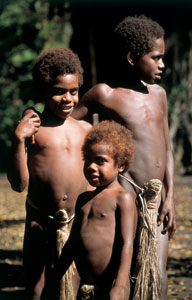

Boys wearing penis gourds, YakelTo my relief, our eighteen-seat Fokker reached Tanna safely. At the airstrip I hitched a

lift in the only vehicle, a battered pick-up whose driver Roy, astonishingly, was going the

length of the sixty-kilometre-long island to within a stone’s throw of Ipeukelvillage,the

stronghold of the bizarre Jon Frum cargo cult I wanted to visit.

My jubilation was premature; luckily, I didn’t know what was ahead.

The rutted road curved through rainforest dotted with thatched huts in roadside clearings. Half-naked ni-Vanuatu people, the indigenous inhabitants of the islands, silently watched us pass. At crossroads near Lenakel the increasingly pitted road climbed inland towards jungle-covered ridges and craggy mountains. Without warning, we reached a high pass. Far below us there was a desolate grey moonscape, where what looked like an atomic mushroom cloud spiralled into threatening, rain-laden skies. This was Mount Yasur (361 metres), one of the world’s most accessible and active volcanoes.

We descended a muddy red track riddled with craters, all that was left of the road that British Army engineers had built in 1980, until, at the volcano’s foot, we reached Lake Isiwi’s barren, treeless shores. Not long afterwards we arrived at Yaneumakel, a hamlet of primitive huts crouching behind adjacent ridges.

Family in Yakel village, Tanna Island, VanuatuContaining Roy’s extended family of over eighty people, it was desperately poor, but,

seeing dusk was approaching, I accepted his offer to stay the night. I was led to a surprisingly

clean mattress in a hut adorned with posters that said ‘VANATU SOSAIETI, BLONG ALL PIPEL - SKUL, WOK, PLEI.’ Shortly, I returned to eat in his hut. In a smoke-blackened corner Thelma,

his wife, crouched over pots of yams steaming on a log fire. Joined by Sloki, his oldest son,

and watched by naked infants who stood at the entrance peeping shyly at me, we ate crosslegged

on the earth. For a while we sat by the smouldering embers, staring at shadows cast

by flickering hurricane lamps and listening to the volcano. It was disconcertingly close, and

its booms and rumbles sounded like jumbo jets taking off . . .